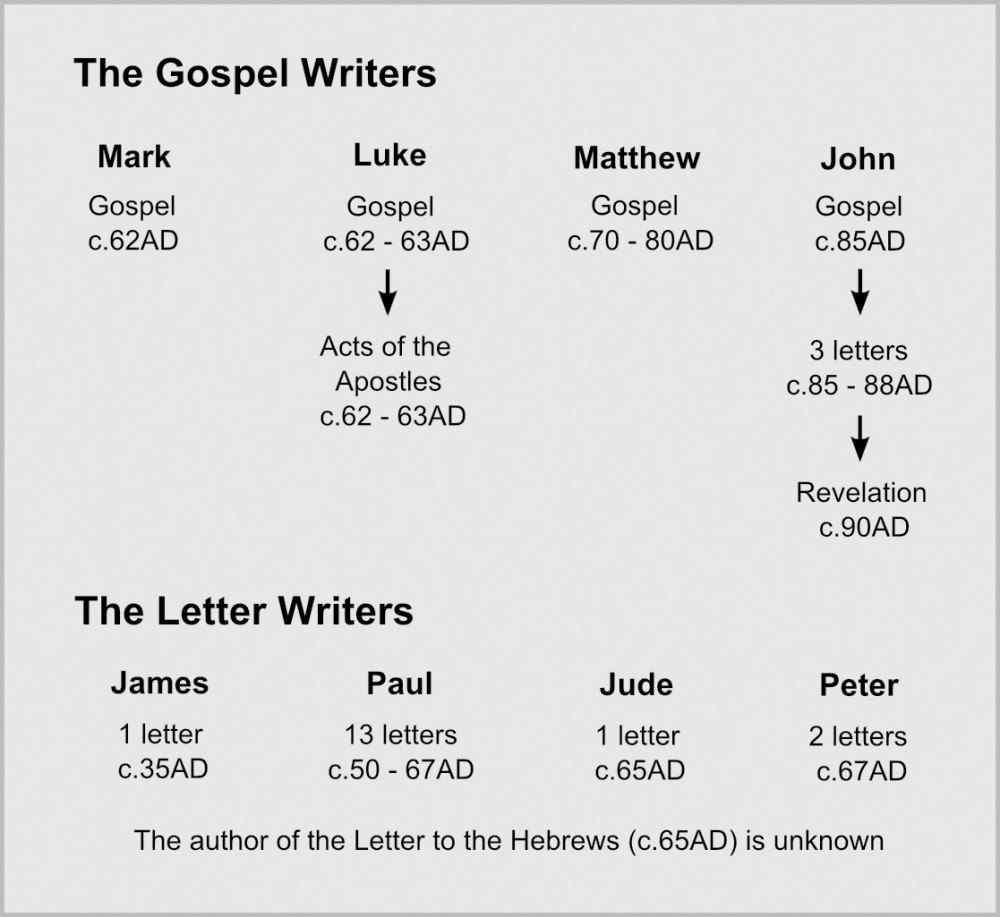

The story of Jesus of Nazareth is told in the New Testament by four different authors (see Fig. 4(c)). The first four books of the New Testament are called ‘gospels’ because they contain the ‘good news’ about Jesus’s life, death and resurrection. The four authors – traditionally identified as Matthew, Mark, Luke and John – had different audiences in mind when they wrote, so the accounts differ quite markedly in approach.

Fig. 4(c) Who wrote the New Testament?

Matthew, Mark and Luke set out to present a description of Jesus’s life and death roughly in chronological order. As, together, they see Jesus’s life in broadly the same way, they are known as the ‘synoptic’ (meaning ‘seeing together’) gospels. John was more concerned with explaining Jesus’s teachings and theology, so he has a more thematic approach and makes little attempt to present his gospel in chronological order.

Mark’s Gospel, the shortest of the four gospels, is widely thought to be the first one to have been written. Over a third of his account concentrates on the events surrounding Jesus’s death and resurrection. It was probably written as early as 62AD (a little over thirty years after the death and resurrection of Jesus) while Mark was staying with Paul in Rome. It is considered to be the earliest gospel because Luke and Matthew appear to borrow a considerable amount of their information from Mark’s narrative. About ninety per cent of Mark’s narrative is repeated in Matthew’s gospel, while Luke includes over half of Mark’s content.

Mark’s early account of Jesus’s life is widely believed to have been written by John Mark, a Jewish member of the early Christian community in Jerusalem, at whose home the first Christian believers met (see Acts 12:12). John Mark, as a teenager, may have known Jesus well. The Upper Room where Jesus’s ‘Last Supper’ was held may have been at Mark’s house. Many scholars think that the young man whom Mark says escaped from the Garden of Gethsemane when Jesus was arrested (see Mark 14:51-52) was John Mark himself.

After Jesus’s death, Mark would have heard first-hand accounts of the life and teachings of Jesus from Peter and the other apostles. As a young man, he travelled across Cyprus with Paul and Barnabas (who was his uncle) in 46AD, before returning to Jerusalem (see Acts 12:25 & 15:37-39). He later spent two years in Rome (60-62AD) when Paul was under house arrest awaiting his trial before Emperor Nero. It is likely that Mark’s Gospel was written around this time, relying, for accuracy, on the accounts that the author had heard from Peter and the other apostles.

Mark was later sent by Paul to the church at Colossae, but Paul asked Timothy to bring Mark back from Colossae to Rome just before his death in c.67AD (see Colossians 4:10 & 2 Timothy 4:11). We know that John Mark arrived back in Rome about this time as Peter sends greetings from Mark in his First Letter to the believers in Asia Minor, written in c.67AD shortly before Peter was executed (see 1 Peter 5:13).

As Mark goes out of his way to explain Jewish customs (see Mark 7:3-4 & 15:42), he was probably addressing an audience that included Gentiles, and may well have written his ‘Good News’ for the believers in Rome.

Rome - where Mark's Gospel was written in c.62AD (Colossians 4:10)

Luke’s Gospel appears to rely heavily on information from Mark’s gospel, as well as containing some additional material from other sources (sometimes referred to by Biblical scholars as ‘Q’ or ‘Quelle’, German for ‘source’). Luke was a Gentile (non-Jewish) doctor, who was a close companion of Paul. He is the only non-Jewish writer whose work is found in the Bible.

He first joined Paul in 51AD at Troas on his second missionary journey (hence the ‘we’ passages that Luke wrote following Acts 16:11) and may well have lived in Philippi where he stayed after Paul and Silas were forced to leave (see Acts 16:40). Some scholars believe that Luke was the ‘Man from Macedonia’ who appeared in Paul’s dream and begged Paul to visit his homeland (see Acts 16:9).

Luke wrote his gospel for a Gentile audience, having been asked for an account of Jesus’s life and teachings by a Roman friend he calls ‘Theophilus’ (‘lover of God’) (see Luke 1:1-4). Luke stresses that Jesus was the saviour of all mankind, whatever their background, their gender or their nationality. He also wrote a second book for ‘Theophilus’ about the Acts of the Apostles (see Acts 1:1-2).

Luke, a Roman citizen, later accompanied Paul from Philippi to Jerusalem in 57AD after his third missionary journey (see the ‘we’ passages following Acts 20:6). He stayed for two years with the believers in Jerusalem and Caesarea, during which time he probably met on many occasions with the Jewish Christian community at the home of John Mark in Jerusalem, and heard many eye-witness accounts of Jesus's teaching, miracles, death and resurrection. Together with Aristarchus, he then travelled with Paul to Rome in 60AD. The next two years were spent with Paul in Rome while Paul was under house arrest awaiting his trial before Nero (see 2 Timothy 4:11).

It was probably during this two years in Rome (60-62AD) that Luke wrote his gospel. He appears to have completed his gospel and the Acts of the Apostles before 64AD, as his account of the apostles’ activities ends before the Great Fire of Rome in 64AD and the outbreak of the Jewish War in 66AD. As the Acts of the Apostles makes no mention of the outcome of Paul’s appeal to Nero that was heard in c.62AD, it was probably written before the result was known.

It follows that Luke probably wrote his gospel and the Acts of the Apostles while staying with Paul in Rome between 60 and 62AD. As it’s likely that John Mark was also staying with Paul around the same time, this may help to explain why large parts of the gospels of Luke and Mark are very similar. Most of the difference in emphasis is accounted for by the fact that Mark’s gospel is written from the perspective of a Jewish Christian, while Luke wrote as a Gentile believer.

Philippi - the home of Luke who wrote his Gospel in c.62-63AD (2 Timothy 4:11)

Matthew’s Gospel is traditionally believed to have been written by Levi, a Jew from Galilee who collected taxes for the Romans, and whose Greek name was Matthew (see Matthew 9:9-13 & Mark 2:13-17). He was one of Jesus’s first ‘apostles’ – his close circle of twelve followers or ‘disciples’ – who were ‘sent out’ with the Good News (see Matthew 10:2-5).

Matthew’s account of Jesus’s life was written between 70 and 80AD primarily for Jewish readers. Its particular emphasis was to persuade its readers that Jesus really was the Messiah or Christ – the ‘anointed one’ promised by the Old Testament prophets. As a result, many passages in Matthew’s gospel set out to demonstrate that Jesus fulfilled the expectations that Jews had of the Messiah in New Testament times (see the feature on Who was the Messiah? in Section 2).

Matthew therefore begins his narrative with a lengthy genealogy to establish that Jesus was a descendent of King David (see Isaiah 9:7 & Matthew 1:1-17). He tells about the ‘magi’ (astrologers or ‘wise men’ from Mesopotamia) who came to Bethlehem after Jesus’s birth seeking the new ‘King of the Jews’ (see Micah 5:2 & Matthew 2:1-12). He then endeavours to show how Jesus was both a ‘prophet like Moses’ (see Deuteronomy 18:15-18 & Matthew 21:11) and the promised ‘Son of Man’ (see Daniel 7:13-14 & Matthew 11:18-19). Matthew’s overriding theme is that Jesus was the ‘Christ’ or ‘Messiah’, foretold by the Jewish prophets, who fulfilled the Law of Moses (see Matthew 5:17-20).

Galilee - the home of Matthew who wrote his Gospel in c.70-80AD (Matthew 9:9)

John’s Gospel is quite different from the other three gospels. It is traditionally believed to have been written by John, one of Jesus’s close circle of twelve apostles, in c.85AD when John, a leader of the Christian community in Ephesus, was an old man. It was written to denounce and disprove a heretical (false) teaching known by scholars as ‘Gnosticism’. Gnostics taught that Jesus was human, but was not divine. John set out to show that Jesus was both human and divine – still a fundamental belief of Christians today.

John wrote three letters to Christian believers between 85 and 88AD in order to denounce the teachings of Gnostics (see 1 John 1:1-4, 2 John 1:7-11 & 3 John 1:3-4), and he probably wrote his gospel very shortly before this in c.85AD. The emphasis of John’s gospel is that Jesus – the ‘Word of God’ who has always co-existed with God – was an amazing revelation of God himself in human form (see John 1:1-14). John’s gospel is therefore unique, and is fascinating to read alongside the other more conventional gospel accounts of Jesus’s life and teaching.

After completing his gospel and his three letters to the daughter churches in the region around Ephesus, John was exiled by the Roman emperor Domitian to the island of Patmos. Here, in c.90AD, he wrote the Book of Revelation – a revelation he received from Jesus Christ about the ‘last days’ (see Revelation 1:1-3). He returned to Ephesus in c.96AD, where he died and was buried.

Ephesus - where John's Gospel was written c.85AD (Revelation 2:1)