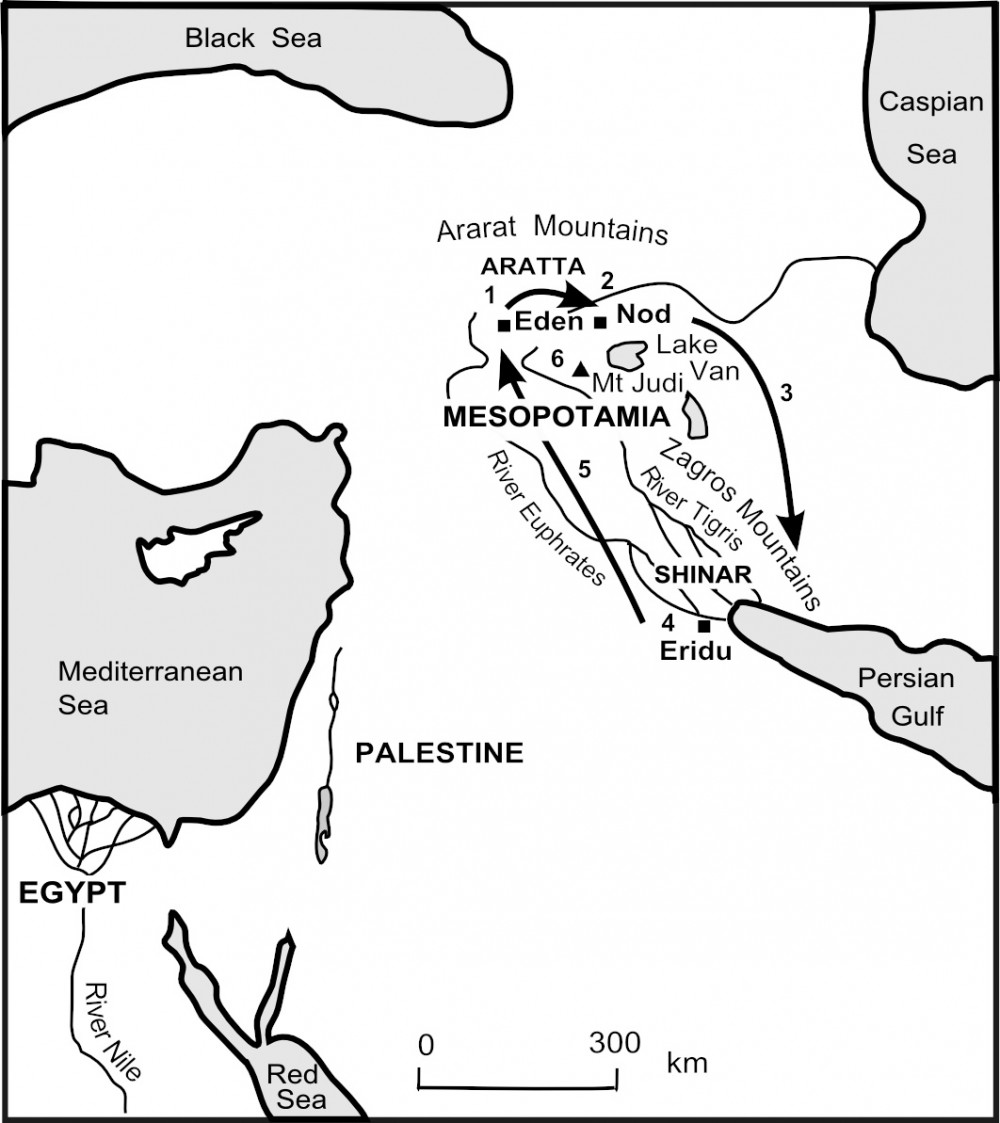

Gen 2:8-9 The story moves to the Garden of Eden, where God provides a suitable dwelling place for the man he has created. “Then the LORD God planted a garden in the east" (that is, east of the Mediterranean world, where the account was written), "in a place called Eden” (Genesis 2:8) (See 1 on Map 35).

Map 35 From Eden to Aratta

The Garden of Eden

Some believe that the Biblical account of the ‘Garden of Eden’ is literally true; many others believe it is a symbolic description of the idyllic conditions and earthly ‘paradise’ that God intended for mankind from the beginning of time.

The location of the Garden of Eden is unclear. The Biblical account suggests that Eden lay in the uplands near the headwaters of the River Tigris and the River Euphrates (see Genesis 2:14 and 1 on Map 35). Eden, however, is the Sumerian word indicating a plain - a flat area where cultivation would be easy. In early Sumerian poetry (which pre-dates the Old Testament), the garden 'paradise' of Dilmun was located in the well-watered plain of Shinar where the two great rivers – the Tigris and the Euphrates – flowed into the Persian Gulf (see 4 on Map 35).

The ‘garden’ of Eden indicates a well-tended enclosed area where food was available in abundance. The word 'paradise', in fact, derives from the ancient Persian word for a garden ('pairidaeza') - literally a 'walled garden'. ‘Eden’ also sounds like the Hebrew for ‘delight’ – it was a delightful place with plentiful fruit trees and abundant animal life.

Eden had plentiful surface water – in stark contrast to Palestine where Jewish readers of the ‘Tanakh’ (the Old Testament) relied on hauling water up from deep wells. Isaac, for example, during a severe drought, dug four wells near Gerar and Beersheba (see Genesis 26:18-25).

Gen 2:10-14 “A river flowed through Eden and watered the garden. From there the river branched out to become four rivers."

The Rivers of Eden

The names of the four headwaters flowing from Eden signify that God’s creation was considered to be at the centre of the known world in ancient times:

The Pishon flowed through the "land of Havilah” (Genesis 2:11). Genesis 10:29-30 and 1 Samuel 15:7 indicate that Havilah was located in south west Arabia; Genesis 25:18 suggests a location in north west Arabia between the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Gulf.

The Gihon flowed through the "land of Cush” (Genesis 2:13). Cush was the name given to the area of north east Africa stretching from Ethiopia to northern Sudan (see Genesis 10:6).

The Tigris flowed “out of Assyria” (Genesis 2:14) (from its source in modern-day Turkey) to southern Mesopotamia (meaning ‘between the rivers’ – between the River Tigris and the River Euphrates in modern-day Iraq).

The Euphrates flowed from eastern Anatolia (in modern-day Turkey) to southern Mesopotamia (in modern-day Iraq).

There is no actual geographical location with four rivers flowing out to all the places identified in Genesis Chapter 2. Rather, these symbolic names indicate that Eden was considered to be at the centre of the ancient world, with important rivers flowing on all sides of it.

The names Pishon and Gihon (which are not mentioned again in the Bible) sound like the Hebrew words for ‘gusher’ and ‘bubbler’. These symbolic names may indicate minor tributaries of the Tigris and the Euphrates in northern Mesopotamia, or may signify major rivers elsewhere. The Jewish historian Josephus, for example, identified the Pishon as the Ganges (and Havilah as India), while he identified the Gihon with the Nile flowing from Cush (Ethiopia).

Gen 2:15-25 In a second account of Creation in Genesis 2, God creates man (see Genesis 2:8) then provides a partner for him (see Genesis 2:21-24), and the man and his wife live happily together in the Garden of Eden.

Many believe that the names given to the man and woman are symbolic names indicating that they represent all mankind. Adam is the Hebrew word for ‘mankind’, while Eve (the ‘mother of all life’) sounds similar to the Hebrew word for life. The brief creation account in Genesis 5:1-2 also stresses God's role in creating all human beings.

Gen 3:1-25 Adam and Eve live an ideal existence in this earthly paradise until they disobey God. They are tricked by a serpent (a symbolic creature representing the deceiver or the 'satan') (see Revelation 12:9) into eating the ‘forbidden fruit’ and are banished from the garden to the land east of Eden as a punishment for going against God’s commands (See 1 on Map 35 above). Life will never be so idyllic again as this first momentous journey begins and they leave the earthly paradise of Eden.

Trees in the Garden of Eden

Genesis 2:9 tells us, “In the middle of the Garden, God put the tree that gives life and also the tree that gives the knowledge of good and evil.”

The concept of the ‘Tree of Life’ as the source of all life was widespread across ancient religions. In Egyptian mythology, for example, the gods Isis and Osiris were said to have sprung to life from the acacia tree of Iusaaset. A ‘tree of life’ is depicted on Assyrian stone panels at Nimrud, while in ancient Persian mythology, the sacred hauma tree is regarded as the source of life.

In contrast, the ‘Tree of Life’ in the Garden of Eden has traditionally been regarded by Christians as a prefiguration of the Cross of Jesus – the source of eternal life which mankind could not partake of until the death and resurrection of Jesus (see Revelation 2:7 & 22:1-3).

The type of tree bearing the knowledge of good and evil – whose fruit Adam and Eve were forbidden to eat – is not specified in the Bible. In the Western world, it has often been regarded as an apple tree, but earlier readers in the Middle East would probably have identified it as a date palm or sycamore fig tree. Adam and Eve were told not to eat the fruit because, “you will learn about good and evil and you will be like God!” (Genesis 3:5)

In the Middle Eastern world of early Old Testament times, sacred trees were common in contemporary Egyptian and Mesopotamian religions, and the deity was often thought to dwell in the tree. The Egyptian sky-goddess Nut was often depicted as a sycamore fig tree, while the goddess Hathor was known as ‘Nebetnehat’ – ‘Lady of the sycamore tree’. The Sumerian god Ningishzida (or Ningizzida), often depicted as a serpent, was thought to live within the tree itself. To eat the fruit of such a tree would be to partake of the life of the god himself – literally, to become like God.