In the Old Testament, the Israelites were given strict instructions to worship the one, true God (Yahweh), and not to worship any foreign gods or idols (see Isaiah 44:6).

The most important commandment in Judaism (quoted by Jesus when asked which was the greatest commandment) is the ‘Shema’: “Shema Yisrael Adonai Eloheinu, Adonai ehad!” (Hebrew, meaning, ‘Hear, O Israel, the LORD our God, the LORD is one!’) (see Deuteronomy 6:4-5 & Matthew 22:35-37).

But many foreign gods and goddesses were worshipped in Israel, and the Old Testament is full of references to foreign deities such as Baal, Ashtoreth, Asherah, Chemosh and Molech.

‘Hear, O Israel, the LORD our God, the LORD is one!’ (Willy Horst)

Baal

When the Israelites invaded Canaan under Joshua in c.1406BC, the Canaanites worshipped local gods known as ‘Baals’ or ‘Baalim’. ‘Baal’ was believed to be the son of ‘El’, the senior god of the Canaanites (‘El’ is the Semitic word for ‘god’ shared by the Israelites and the Canaanites). Baal means ‘Lord’ or ‘Master’.

The gods (or ‘Baalim’) of individual cities were often known by the name of the place, hence the Baal of Peor (see Numbers 25:3), Baal Meon (see Joshua 13:17), and Baal Hazor (see 2 Samuel 13:23). But the word ‘Baal’ also became a personal name to indicate the supreme fertility god of the Canaanites – the ‘Lord of the Earth’, who ensured good crops in this agricultural society.

The Baals were endemic in Canaan when the Israelites arrived, but the spread of Baal worship owed much to inter-marriage with foreign women who worshipped the Baals. The most celebrated example of this was when King Ahab married the Phoenician princess Jezebel in around 874BC. Jezebel imported the trappings of her own religion (including the priests of Baal Melquart – the Baal of Tyre, her own hometown) and persecuted the prophets of Yahweh (see 1 Kings 16:30-33).

Elijah’s encounter with the prophets of Baal on Mount Carmel (see 1 Kings18:16-40) was just one of many head-on clashes between worshippers of Yahweh and the followers of Baal. King Jehu slew many prophets of Baal in the Temple of Baal at Samaria in 842BC (see 2 Kings 10:18-31), while King Josiah later made strenuous efforts to rid the Israelite nation of Baal worship in 624BC (see 2 Kings 23:4-7).

Baal worship not only involved ritual prostitution and degrading sexual practices common to many fertility cults, but it also included child sacrifice (see Jeremiah 19:5). It was often practiced in association with the cult of the goddesses Ashtoreth and Asherah (see below).

Mount Carmel, where Elijah defeated the prophets of Baal

Baal Zephon (meaning ‘Lord of the North’) was the name of a city in the north-eastern Nile Delta, where the Israelites camped during their Exodus from Egypt (see Exodus 14:2). It was named after the god of Egypt’s northern neighbours, the Canaanites.

Baal Gad was the name given to a religious ‘high place’ of worship below the summit of Mount Hermon. It marked the northernmost boundary of the lands conquered by Joshua. At that time, it was called Baal Gad after the pagan god who was worshipped there (see Joshua 11:16-17). It was later renamed Caesarea Philippi. Jesus was in this area of pagan worship when he asked his disciples, ‘Who do people say I am?’ and Peter answered, “You are the’Christ’ (the ‘Messiah’), the Son of the living God” (Matthew 16:13-16).

Baal Berith (meaning, ‘Lord of the covenant’) was the Canaanite god of Shechem. It was at the temple of Baal Berith (or El Berith) at Shechem that Abimelech, the first Jewish king, burnt to death the citizens of Shechem who opposed his tyrranical rule (see Judges 8:33 & 9:46-49).

Baal Zebub or Beelzebub (meaning ‘Lord of the flies’) was the god of Ekron whom King Ahaziah was prevented from consulting by the intervention of Elijah (see 2 Kings 1:1-16). The name ‘Beelzebub’ was probably a Hebrew corruption of the Canaanite name ‘Beelzebul’ (meaning ‘Lord of the high place’). In the New Testament, the Pharisees denounced Jesus for casting out demons in the name of “Beelzebub, the prince of demons” (see Matthew 12:24).

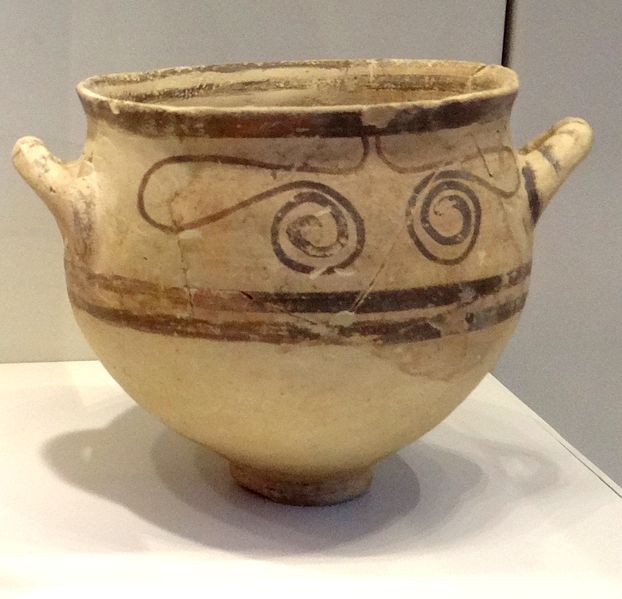

A Philistine pottery drinking bowl from Ekron (Hanay)

Around 940BC, as King Solomon grew older (and less wise), he became increasingly involved in the worship of foreign gods imported into Israel by his seven hundred foreign wives (see 1 Kings 11:1-6). Amongst other foreign gods, he implicitly gave royal sanction to the worship of Ashtoreth, Molech and Chemosh.

Ashtoreth (Ishtar or Astarte)

Ashtoreth, the consort of Baal, was a Canaanite fertility goddess who had attracted the worship of some Israelites ever since the invasion of Canaan in c.1406BC (see Judges 2:10-13 & 10:6). In earlier days, Ashtoreth Karnaim was a centre of Ashtoreth worship in the time of Abraham (see Genesis 14:5). The worship of Ashtoreth had become widespread among the Israelites by the time of Samuel in c.1024BC (see 1 Samuel 7:3-4). After King Saul was killed by the Philistines at the Battle of Mt Gilboa in c.1011BC, his armour was placed in the Temple of Ashtoreth at Beth Shean (see 1 Samuel 31:8-10).

The excavation of clay images showing a naked female at numerous archaological sites confirms that the worship of Ashtoreth was widespread during the time of the ‘Judges’ and throughout the reigns of the kings of Israel and Judah. As well as male and female ritual prostitution, the cult of Ashtoreth also involved child sacrifice.

Statuette of Ashtoreth in the Louvre (Marie-Lan Nguyen)

Asherah

Asherah, another Canaanite fertility goddess, was believed to be the wife of ‘El’, the chief god of the Canaanites. In common with the cult of Ashtoreth, the veneration of Asherah was often associated with the worship of Baal (see Judges 6:25 & 2 Kings 23:4). ‘Asherah poles’ were symbols of fertile, fruit-laden trees and of the goddess Asherah herself. They were often erected near pagan altars (see 1 Kings 16:32-33) and adjacent to other ‘sacred trees’ (see 1 Kings 14:22-24).

The worship of sacred trees was common in Canaan before the Israelite conquest. Abraham and Jacob both visited the sacred grove at Shechem (see Genesis 12:6 & 35:4), while the Tomb of the Patriarchs at Hebron was built near the sacred trees of Mamre (see Genesis 18:1, 23:17 & 25:9). The toleration of these ‘sacred trees’ and their adoption by the Israelites was another major contributor to their fall from God’s grace (see Isaiah 1:29).

Tomb of the Patriarchs at Hebron (Zairon)

Chemosh

Chemosh was the god of Moab, the land to the south east of Judah. The Moabites are recorded as worshipping Chemosh in the time of Moses (see Numbers 21:29), but it was not until King Solomon built a ‘high place’ (an altar) to Chemosh on the Mount of Olives, facing Jerusalem, that the religion was officially sanctioned in Israel (see 1 Kings 11:7). This ‘high place’, built in c.940BC, was not removed until King Josiah desecrated the ‘Mount of Corruption’ (the Mount of Olives) in 624BC (see 2 Kings 23:13).

The worship of Chemosh was another pagan religion that practised the ritual sacrifice of children. After the death of King Ahab of Israel in 852BC, King Mesha of Moab rose in rebellion, but was soundly defeated by the Israelites. As a final act of desperation, he stood on top of the city walls of Kir Hareseth and sacrificed his eldest son and heir, in full view of the horrified Israelite soldiers who looked on (see 2 Kings 3:27). The worship of Chemosh was decried nearly three hundred years later by the prophet Jeremiah, in exile in Egypt following the fall of Jerusalem in 587BC (see Jeremiah 48:13).

The 'Mount of Corruption' (Mount of Olives), where Chemosh was worshipped (Yair Haklai)

Molech

Molech, the God of Ammon, was also introduced into Israel by Solomon and his Ammonite wives with their foreign retinues (see 1 Kings 11:5). Prior to this, any Israelite or foreigner who sacrificed his children to Molech was guilty of an abomination in the eyes of Yahweh and was put to death (see Leviticus 20:1-5).

After the official toleration of this foreign religion, children were burned alive on the altars of Topheth, in the Valley of Hinnom, immediately south of the city walls of Jerusalem (see 2 Kings 23:10 & Jeremiah 32:35). King Ahaz of Judah sacrificed his own sons in the fires of Gehenna (the name, often translated ‘hell’, adopted by the Jews to describe the Valley of Hinnom), as did King Manasseh (see 2 Chronicles 28:3 & 2 Kings 21:6).

It was left to King Josiah to destroy the 'high places' of Molech during the revival he began in Judah in 624BC (see 2 Kings 23:10-13), though the condemnations of Ezekiel, Malachi and Zephaniah all atest to smouldering pockets of resistance to Josiah’s religious reforms during the following century. (See Ezekiel 23:37-39, Malachi 2:11 & Zephaniah 4-5)

The Valley of Hinnom, where children were sacrificed to Molech

Other foreign gods.

Other deities worshipped by the Israelites included the gods of Egypt and the gods of Babylon.

The Egyptians worshipped the Sun god, Re (or Ra), while the Egyptian pharaohs were considered to be divine servants of the Sun (Re), reflecting his brilliance. Three of the 4th dynasty pharaohs who built pyramids at Geza, Djedef-re, Khaf-re and Menkau-re began the practice of bearing the name of Re, and thus carrying his divine authority and power.

When King Solomon married the daughter of Pharaoh Haremheb in c.970BC, he built a separate palace for her, immediately north of Jerusalem, so that her religious practices would not ‘pollute’ the City of David (see 1 Kings 9:24). Later in his reign, the worship of the Sun and the stars become sanctioned by Solomon, and the practice of Sun worship was only eventually prohibited by King Josiah in 624BC (see 2 Kings 23:4-5).

Prior to this, horse-drawn chariots representing the daily progress of the Sun god across the heavens had been installed at the entrance to the Temple in Jerusalem (see 2 Kings 23:11). The Israelites, however, continued to dabble in Egyptian religious practices, and after the fall of Jerusalem in 587BC, Jeremiah rebuked those in exile in Egypt for worshipping the ‘Queen of Heaven’ (Isis or possibly Ashtoreth) and Amon (Amun), the ‘god of Thebes’ (see Jeremiah 44:15-19 & 46:25).

The 'Queen of the Night' - the Babylonian goddess Ishtar (Hispalois)

The principal gods of the Babylonians were Marduk (also referred to as Bel, meaning ‘Baal’ or ‘Lord’) and Nebo. Images (or idols) of these gods were paraded through the streets during religious festivals (see Isaiah 46:1, Jeremiah 50:2 & 51:44). The story of Daniel, Bel and the Snake in the Apocrypha (and in the Greek version of the Hebrew scriptures, the Septuagint) tells of the deceptions and fraudulant claims perpetrated by the priests of the temple of Bel.

Like the Egyptian pharoahs and many of the Israelite monarchs, the kings of Babylon often took a name incorporating the name of their god. Daniel served at the court of Bel-shazzar (meaning ‘Bel protect [the king]’) (see Daniel 5:1), and was given the title Bel-te-shazzar (‘Bel protect him’) (see Daniel 5:12). When asked to interpret Belshazzar’s dream, Daniel critisised the king for worshipping “gods of silver, gold, bronze, iron, wood and stone that are not really gods; they cannot see or hear or understand anything.” (Daniel 5:23) Daniel regarded this as ample justification for Belshazzar’s defeat by Darius, the king of the Medes and Persians (see Daniel 5:26-31).